Dancing with Ghosts: Adriel Visoto

Upon entering the house,

I felt I could cut the air with a knife.

Two glasses.

I served the other before serving myself.

If it’s not possible to defeat the ghosts,

I could sit, toast, and dance with them.

And so I did.

Text by Jean-Marie Reynier

Adriel Visoto (born in 1987 in Brazópolis, Brazil, lives and works in São Paulo) presents “Dancing with Ghosts”, his first exhibition in Switzerland, at Fabienne Levy Gallery in Lausanne and Geneva. In this exhibition, he explores the persistence of images and memories. A diffuse presence inhabits his paintings: they do not freeze a moment in time, but rather accompany it, transform it, carry it forward.

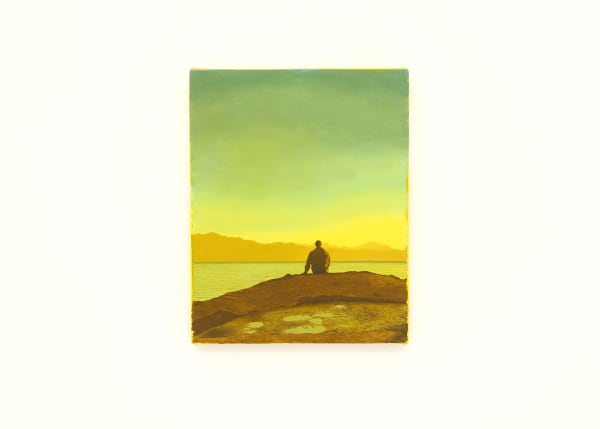

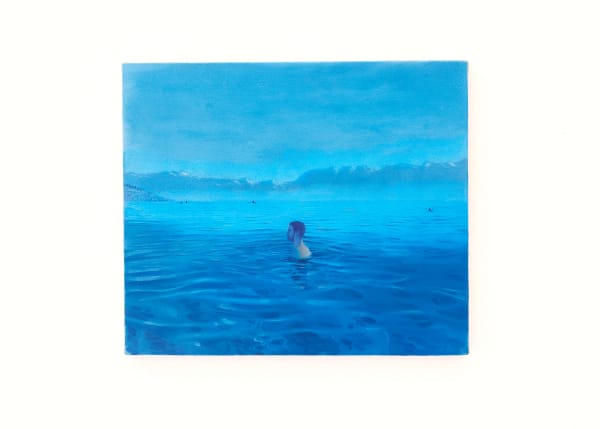

Through a kind of alchemical realism, grass rises from the earth in his canvases before being buried under snow; the mountains of Lake Geneva appear only to fade into mist. His painting seems to follow the rhythm of the seasons, inscribing each image within a shifting cartography of memory. The grass grows, layer by layer, until it dissolves beneath a white veil—painting here becomes an act of accompaniment rather than fixation. Each image is built patiently, through superimpositions that veil without ever fully erasing. What disappears leaves an imprint; what emerges still bears the trace of what came before.

This approach is also present in Visoto’s gesture itself: he paints with an extremely fine brush, sometimes requiring magnifying lenses. Far from anecdotal, this technical detail speaks to an almost obsessive attention to material and detail, a work of patience where each stroke seems suspended in time. The glaze, applied in successive translucent layers, creates a vibrant depth, an oscillation between emergence and retreat. But he also works through subtraction: covering, veiling, softening—as if each new layer still carried the memory of what lies beneath.

What remains of an image when it fades?

Interior and exterior dissolve into one another. Even outdoors, we remain immersed in an intimate space where light draws invisible thresholds. Through this interplay of transparency and lingering presence, Visoto evokes the passage of time and the way images saturate the places they pass through.

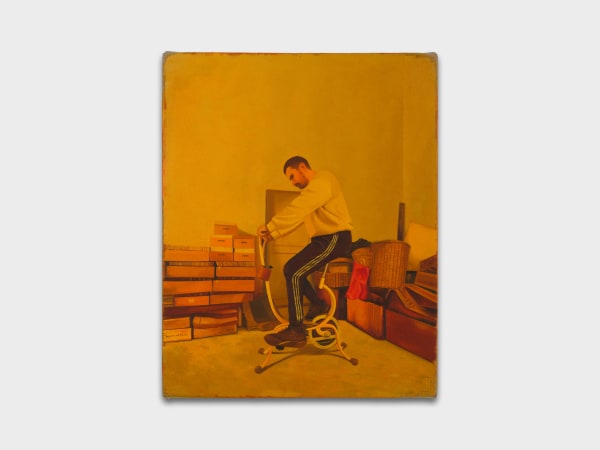

If landscapes and gardens express a relation to the world, interior scenes—warmer, more embodied—speak of solitude, intimacy, autobiography. Everyday objects appear fragmented, partially veiled, as if seen through the haze of a dream or memory. These domestic spaces, bathed in soft light, shelter blurred presences, barely sketched faces, self-portraits held at a distance. There is a kind of restrained self-exposure here, where the gaze turns inward—toward what is slowly revealed in the repetition of gestures, in the silent observation of things. These works speak to a sense of home that is as much mental as it is physical: a space of withdrawal, of reflection, but also of discreet revelations of intimacy.

His monochrome drawings extend this exploration of thresholds. The line lingers on light and the gradual erasure of form. Here, contours waver, silhouettes drift away, and the material absorbs more than it defines. Each image is a fragile balance between what emerges and what fades, like a ghost in a reinhabited house. Even the self-portraits oscillate between presence and dissolution. The human figure merges with matter, becoming imprint rather than subject. To look at his work is to question what remains, what slips away.

In this attention to the slow movement of things, there is something of Giorgio Morandi. Not in form, but in the way the image is awaited, allowed to surface through sedimentation. Morandi, who during the war painted, tirelessly, the dust settling on his bottles—an act of silent resistance to the violence of History. His painting was not a refuge, but a form of engagement: a refusal to yield to the urgency of the world, a way of letting time work on objects, of watching them until they merged with their own disappearance. The same is true of his landscapes in Grizzana, where the hills and low houses, seen again and again, become an interiority. The outside is absorbed, and the line between mental and physical space becomes uncertain.

In Visoto’s work, this same porosity is at play: his landscapes are not depictions but places traversed by memory. One has the strange sensation of being inside an exterior space. They are as much spaces of recollection as physical sites. Through them, he brings into tension what is seen and what is felt, what endures and what vanishes. The exhibition, shown across both locations of Fabienne Levy Gallery—Lausanne and Geneva—offers a physical echo of this duality. In Lausanne, the hanging focuses on landscapes, gardens, and open spaces, bathed in greens and blues, expressing a relation to the outside world, to seasonal change, and to the inscription of time in nature. In Geneva, interiors, domestic scenes, and self-portraits occupy the space, in warmer compositions filled with reds, ochres, and browns. This chromatic distribution—cool outside, warm inside—underscores a tension between openness and withdrawal, between vastness and intimacy. It subtly guides the viewer’s gaze from a world shaped by landscape to one haunted by inner memory, in a gradual shift from the universal to the autobiographical.

The ghosts here are not spectres in the traditional sense, but latent images—imprints of the past that persist in the present. Like the afterimage that lingers in the eye after staring at the sun. To look at an Adriel Visoto painting is to enter a space where everything is both here and retreating, where each thing seems to await its own disappearance. Painting becomes a fragile threshold, a space where presence and absence merge.